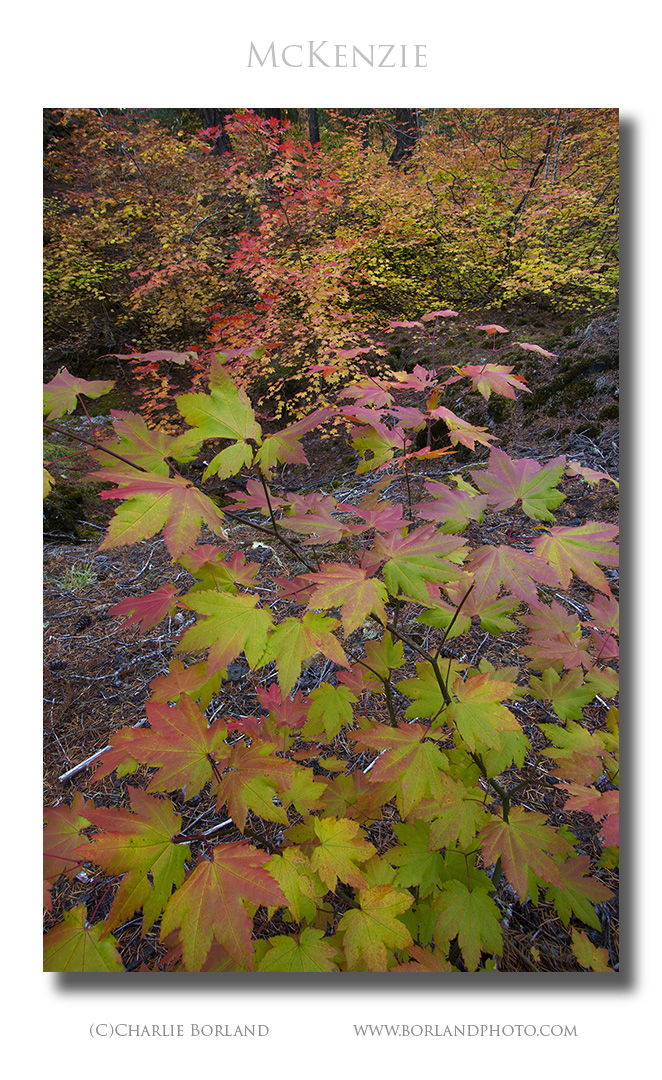

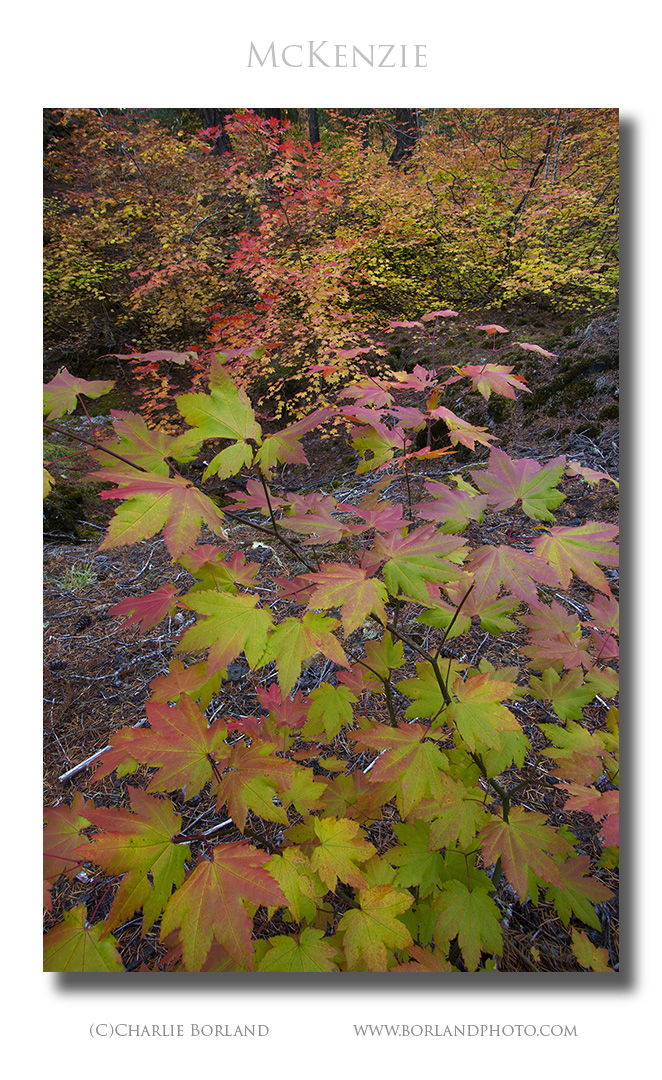

Photographing this image made me realize that fall color that we all love and cherish photographing, is not all about trees.

While I was photographing the amazing aspens in Colorado, I found amazing color closer to the ground.

These plant species, as best as I recall, were not more than 5-6″ across from left side the right side and literally were ground cover.

I dont know what they are but it look to me that they were having their own fall color transformation. The icing on the cake so to speak, literally, is that light coating of frost that added the edges and some white sparkles to the leaves.

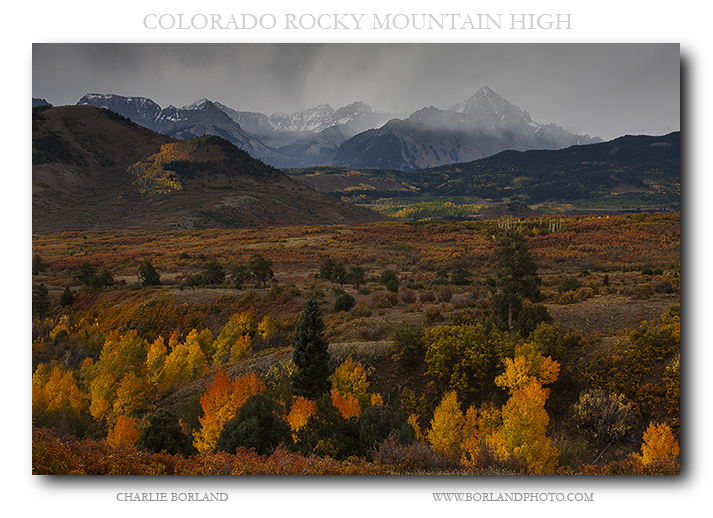

When photographing wide-angle landscapes, often the goal is to make sure everything is in sharp focus. The reason is that usually, we do not like to look at out of focus areas of our scenes. While that shallow depth of field can be a powerful technique to get viewers to look at something in your composition that deserves all the attention, wide-angle landscapes can be more powerful when everything is sharp.

When photographing wide-angle landscapes, often the goal is to make sure everything is in sharp focus. The reason is that usually, we do not like to look at out of focus areas of our scenes. While that shallow depth of field can be a powerful technique to get viewers to look at something in your composition that deserves all the attention, wide-angle landscapes can be more powerful when everything is sharp. When photographing wide-angle landscapes, often the goal is to make sure everything is in sharp focus. The reason is that usually, we do not like to look at out of focus areas of our scenes. While that shallow depth of field can be a powerful technique to get viewers to look at something in your composition that deserves all the attention, wide-angle landscapes can be more powerful when everything is sharp.

When photographing wide-angle landscapes, often the goal is to make sure everything is in sharp focus. The reason is that usually, we do not like to look at out of focus areas of our scenes. While that shallow depth of field can be a powerful technique to get viewers to look at something in your composition that deserves all the attention, wide-angle landscapes can be more powerful when everything is sharp.